February 2016

Emanuele Sinagra, Giancarlo Pompei, Giovanni Tomasello, Francesco Cappello, Gaetano Cristian Morreale, Georgios Amvrosiadis, Francesca Rossi, Attilio Ignazio Lo Monte, Aroldo Gabriele Rizzo, and Dario Raimondo

Abstract

Low-grade intestinal inflammation plays a key role in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and this role is likely to be multifactorial. The aim of this review was to summarize the evidence on the spectrum of mucosal inflammation in IBS, highlighting the relationship of this inflammation to the pathophysiology of IBS and its connection to clinical practice. We carried out a bibliographic search in Medline and the Cochrane Library for the period of January 1966 to December 2014, focusing on publications describing an interaction between inflammation and IBS. Several evidences demonstrate microscopic and molecular abnormalities in IBS patients. Understanding the mechanisms underlying low-grade inflammation in IBS may help to design clinical trials to test the efficacy and safety of drugs that target this pathophysiologic mechanism.

Core tip: Low-grade intestinal inflammation plays a key role in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome, and this influence is likely multifactorial. Several evidences showed microscopic and molecular abnormalities in large subsets of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the low-grade inflammation in this disease may help to design clinical trials to test the efficacy and safety of drugs that target this pathophysiologic mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic, relapsing, and remitting functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel habits that lack a known structural or anatomic explanation[1].

IBS consists of a set of altered bowel habits over a period of time and includes abdominal pain and discomfort. IBS is one of the most common diagnoses in primary care, accounting for approximately 12% of all visits[2]. In addition, a survey conducted by Russo et al[3] found IBS to be the most common functional gastrointestinal diagnosis, comprising 35% of all outpatient referrals to gastroenterologists[2,3]. Therefore, IBS is also the most common diagnosis for gastroenterologists, accounting for 20%-50% of patient visits[2,4].

With regard to the sex-related prevalence of IBS, in Western countries, the prevalence of IBS in female patients outnumbers that in male patients by 2:1[5,6]. Furthermore, the ratio of female to male IBS sufferers in the non-patient population is 2:1, and within the patient population who seek consultations with primary care physicians, females outnumber male patients by 3:1[5,7]. Finally, in tertiary-care settings, the number of female IBS patients is four- to five-times higher than the number of males[5-8]. This prevalence should not only be strictly attributed to sex, but also to gender-related differences in healthcare-seeking behavior and sociocultural characteristics that vary between men and women with IBS as well as among different cultures[5,6].

According to the Rome III criteria, IBS is defined based on the presence of recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least three days per month in the past three months associated with two or more of the following: (1) improvement with defecation; (2) onset associated with a change in frequency of stool; and (3) onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool. These criteria should be fulfilled for the previous three months with symptom onset at least six months before diagnosis[9].

Rome III criteria subtype IBS according to the predominant bowel habit as IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), mixed type, and unclassified[9]. To this end, the definition of bowel-habit type is based on the patient’s description of the stool form by referring to the Bristol Stool Scale[10]. Furthermore, IBS patients can be divided into two categories: sporadic (nonspecific) and postinfectious (PI-IBS) inflammatory bowel disease-associated[11,12].

IBS symptoms cannot be explained by structural abnormalities, and specific laboratory tests or biomarkers are not available for IBS. Therefore, IBS is classified as a functional disorder whose diagnosis depends on the history of manifested symptoms[13].

The cause of IBS is unknown, but a single factor is not likely to be responsible for the several presentations of this complex disorder[1]; new fields of research in this area include mucosal inflammation, postinfectious low-grade inflammation, genetic and immunologic factors, alteration of the human microbiota, alterations of the intestinal permeability, and dietary and neuroendocrine factors[13]. Usually, routine histologic examinations do not show significant colonic mucosal abnormalities in the majority of IBS patients; however, recent quantitative histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural analyses have indicated subtle organic alterations in these patients.

This literature review aims to summarize the findings relating the spectrum of mucosal inflammation to IBS, highlighting their relationship to the pathophysiology of IBS and their connections, if any, to clinical practice.

RESEARCH

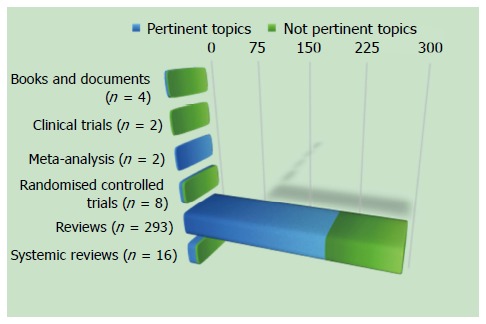

We carried out a bibliographic search in MEDLINE for the period of January 1966 to July 2015, and focused on identifying publications describing an interaction between inflammation and IBS. The keywords used were: irritable bowel syndrome, inflammation, mucosal inflammation, pathology, mast cells, neuroendocrine cells, immune cells, intestinal permeability, and enteric nerves. The inclusion criteria to select articles were based on design (systematic reviews, meta-analysis, clinical trials, and experimental studies on animals) and population (adult patients > 18 years of age). We excluded articles not pertinent to this topic.

According to the aforementioned criteria, we found 305 studies, and we excluded 100 studies because they were not pertinent to this topic (Figure (Figure 1).

ROLE OF ENDOSCOPY IN IBS

According to the American Gastroenterology Association, “a colonoscopy is recommended for patients over age 50 years (due to higher pretest probability of colon cancer), but in younger patients, performing a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy is determined by clinical features suggestive of disease (e.g., diarrhea, weight loss), and may not be indicated”[14].

However, the British guidelines suggest that, “given the high frequency of colonic cancer in the population at large, an examination of the colon is advisable for a change in bowel habit over the age of 50”; the authors of these guidelines highlighted that, “as IBS patients have no increased risk of colon cancer, advice on screening for this is no different from the general population”[15].

More recently, Japanese guidelines suggested that “colonoscopy has a diagnostic value, not only for excluding organic diseases but also for supporting the existence of pathophysiology compatible to IBS due to visceral hypersensitivity to colonoscopic procedures and colonic spasms”[16].

A prospective, multicenter study performed by Ishihara and coworkers[17] aimed to determine the presence of organic colonic lesions in IBS patients. Their study showed that the prevalence of organic colonic diseases in IBS patients was at an acceptably low level, thus showing that the Rome III criteria are specific for the diagnosis of IBS. Conversely, another study performed by Hsiao and coworkers[18] demonstrated that IBS was not associated with the development of colon cancer in Taiwan.

Despite these recommendations, a recent Korean survey indicated that colonoscopy was the most commonly required test (79.5%) in IBS patients[19], whereas a study performed by Lieberman and coworkers[20] to evaluate trends in the utilization and outcomes of colonoscopy in the United States from 2000 to 2011 showed that the most common reason for colonoscopy in patients aged < 50 years was the evaluation of symptoms, such as IBS (28.7%), together with bleeding or anemia (35.3%).

Based on these updated data, IBS still represents the majority of colonoscopic biopsies seen by pathologists[21] that are usually considered either normal or near to normal on routine histologic examination. These findings provide valuable information to the physician who is suspecting a diagnosis of IBS. However, the pathologists must be aware of variations in normal tissue as well as artifacts that may result from bowel preparations or the biopsy procedure in order to not to report these variations as abnormal. Furthermore, the pathologists must consider subtle morphologic changes reported in the intestinal mucosa in IBS and associated with chronic inflammatory cells, mast cells, enteroendocrine cells, and enteric nerves[22].

CONCLUSION

Low-grade intestinal inflammation plays a key role in the pathophysiology of IBS, and this role is likely multifactorial[202]. Several studies demonstrated microscopic and molecular abnormalities in IBS patients[202,203].

The above-reported evidence provides a rationale to test the efficacy of intestinal anti-inflammatory compounds in patients with IBS. Previously, treatment with corticosteroids was found to be ineffective in PI-IBS patients[204]; however, MC stabilizers have produced promising results, particularly in IBS-D, suggesting that immune mechanisms and MCs are involved in the generation of IBS symptoms[205,206]. Based on this approach, Clarke and coworkers[207] recently conducted a phase 3, multicenter, tertiary setting, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with Rome III-confirmed IBS to evaluate the efficacy and safety of mesalazine in patients with IBS. In this study, mesalazine treatment was not superior to placebo based on the study primary endpoint (68.6% vs 67.4%, 95%CI: 12.8-15.1, P = 0.870). However, the placebo response was high in this trial and this study enrolled both male and female subjects and patients with mild symptoms[207], which likely masked drug efficacy. Furthermore, a subgroup of patients with IBS showed a sustained therapy response and benefits from mesalazine therapy[207].

As mentioned above, abnormalities in the enteric nervous system of the gut may alter digestion, gastrointestinal motility, and visceral hypersensitivity, which contribute to symptom onset and play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of IBS[12].

The enteric nervous system of the gut seems to be affected by genetic differences, diet, intestinal flora, and inflammation[12]. For example, the food content of FODMAPs and fibers, which interacts with the intestinal flora and drives subsequent fermentation, may increase intestinal osmotic pressure to induce hormonal and serotonin release[12]. Targeting these known factors may improve the control of IBS symptoms by acting on mechanisms that trigger these symptoms and regulate the pathophysiology of IBS. Finally, probiotics have also been found to be effective in select IBS patients, as suggested by several recent systematic reviews, guidelines and meta-analyses, by improving intestinal permeability[208-212].

In conclusion, a high proportion of IBS patients show low-grade inflammation, which is a multifactorial process, in the intestinal mucosa. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the low-grade inflammation in IBS may allow the design of clinical trials that test the efficacy and safety of drugs that target the pathophysiologic mechanism of this disease.