April 2018

Iacopo Chiodini1,2 and Mark J Bolland

Abstract

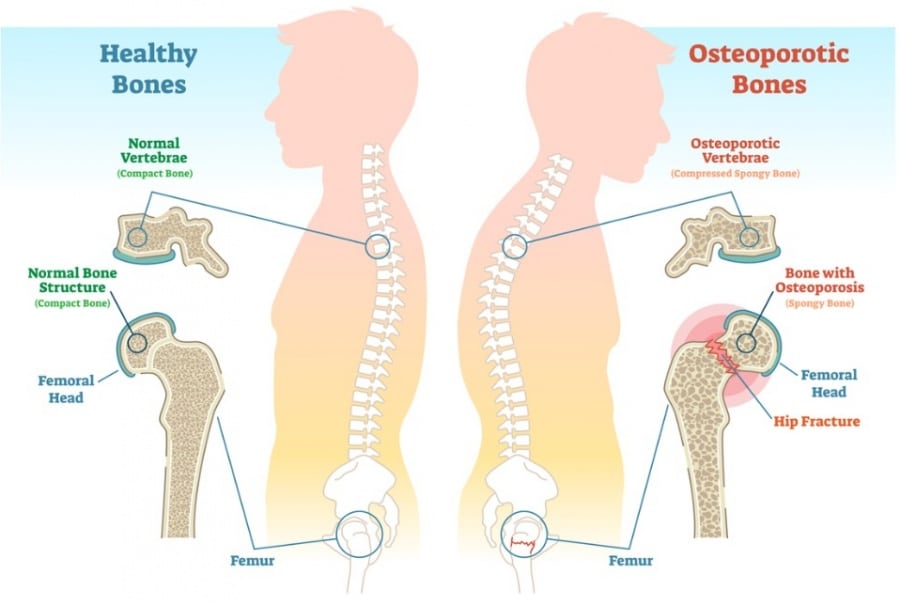

Osteoporosis and fragility fractures are important social and economic problems worldwide and are due to both the loss of bone mineral density and sarcopenia. Indeed, fragility fractures are associated with increased disability, morbidity and mortality.

It is known that a normal calcium balance together with a normal vitamin D status is important for maintaining well-balanced bone metabolism, and for many years, calcium and vitamin D have been considered crucial in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.

However, recently, the usefulness of calcium supplementation (alone or with concomitant vitamin D) has been questioned, since some studies reported only weak efficacy of these supplementations in reducing fragility fracture risk.

On the other hand, besides the gastrointestinal side effects of calcium supplements and the risk of kidney stones related to use of co-administered calcium and vitamin D supplements, other recent data suggested potential adverse cardiovascular effects from calcium supplementation.

This debate article is focused on the evidence regarding both the possible usefulness for bone health and the potential harmful effects of calcium and/or calcium with vitamin D supplementation.

Introduction

The burden of osteoporotic fractures is an important social and economic problem worldwide and both the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) and the reduction of muscle function are major causes of these health-defining events (1, 2, 3). Fragility fractures are associated with important disability, increased morbidity and a 20% increased mortality (2).

For many years, a normal calcium balance together with normal vitamin D status has been considered crucial for maintaining well-balanced bone metabolism and in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis (4, 5). However, in recent years, the usefulness of calcium supplementation (alone and with concomitant vitamin D supplementation) has been questioned, since some studies reported only weak efficacy of these supplementations in reducing fragility fracture risk (6, 7, 8).

Concomitantly, besides the known gastrointestinal side effects of calcium supplements and the risk of kidney stones related to use of co-administered calcium and vitamin D supplements, other evidence suggested potential adverse cardiovascular effects from calcium supplementation (9, 10, 11).

The aim of this debate article is to focus on the evidence regarding both the possible usefulness for bone health and the potential harmful effects of calcium and/or calcium with vitamin D supplementation.

Calcium supplementation in osteoporosis: useful (Iacopo Chiodini)

Calcium intake

The concept of the usefulness of calcium supplementation for bone health is based on the fact that in humans, as in other mammals, the bone-parathyroid-kidney-ileum axis is finely tuned for the maintenance of physiological calcium and phosphorous levels and the renewal of bone tissue (12).

The fact that at bone level the type 1 collagen matrix is strengthened with the apposition of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals supports the idea that an adequate calcium status is crucial for bone health (13). The dietary calcium intake may be adequate in most individuals, but, there is evidence that in subjects with inadequate calcium and vitamin D intake, the supplementation strategies are useful for preventing osteoporosis-related fragility fractures (14, 15).

Indeed, in the presence of inadequate calcium intake and/or vitamin D production, the latter being fundamental for a proper intestinal calcium absorption, the incipient hypocalcemia leads to a secondary hyperparathyroidism, increased bone turnover, bone loss and increased facture risk (16).

Interestingly, in turn, vitamin D levels appear to be dependent on calcium intake at or above recommended levels (17).

Moreover, calcium is fundamental even for the muscle physiology and in the skeletal–muscle interaction. Indeed, within the muscle cells, the contraction and relaxation of myosin fibers and the glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolisms have been suggested to be regulated by calcium levels (18, 19). Therefore, the adequate calcium status is important for both bone and muscle.

These considerations explain the high number of studies investigating both the calcium intake in the different populations and the usefulness of calcium and vitamin D supplementation strategies for preventing fragility fractures.

However, it is important to note that the dietary calcium intake is very different among the various populations around the world, and, therefore, the calcium supplements may be of importance for bone health in some countries but much less in others (20). For example, in a study in the United States, less than one-third of women aged 9–71 years had an adequate intake of calcium from their diet alone and even among supplement users (75% of cases) less than 50% of subjects achieved the recommended calcium intake (21).

In a study on about 370 Italian postmenopausal women, the mean daily calcium intake was about 600 mg/day and the 20% of subjects were taking less than 300 mg/day of calcium from dairy products (22). In keeping, in a more recent study in a population of Italian patients with type 1 diabetes, the 50% of men and 27% of women showed a calcium intake below the threshold recommended for the Italian general population (23).

At variance, for example, in two studies on non-osteoporotic men in New Zealand conducted by the group of the coauthor of the present article, the mean calcium intake was about 800 mg/day (24, 25). Further complicating matters, the national recommendations on calcium intake for different ages and genders vary worldwide (20), being for example between 1000 and 1300 mg/day in those from the US National Institutes of Health (26) and between 700 and 1000 mg/day in those from the National Osteoporosis Society (27).

In general, even if these latter recommendations defines 400 mg/day as the lowest amount of calcium required to maintain a healthy skeleton (28), the adequate calcium supplementation for bone health is still a matter of debate, and it is influenced by several factors, such as age and vitamin D levels (17).

It is clear, therefore, that the different calcium intake among the different populations may be an important confounding factor in interpreting the results of the studies on the effect of calcium supplements on bone, since data from randomized controlled trials were not able to be adjusted for baseline personal calcium intake without making subgroups analyses with the consequent loss of the randomized design (6).

Other important confounding factors in the interpretation of these studies are that the different lifestyle and social habits may have influenced the outcomes. For example, it is possible that calcium and other supplements are used by patients with very poor health, with the hope of improving daily activities and quality of life.

On the other hand, the use of calcium supplements may be frequent among the very healthy subjects with lifestyle and other dietary habits associated with low morbidity and mortality (6). It is possible, therefore, that the small effect of calcium supplements that can be appreciated at the population level, is, in fact, derived from an important effect in a small number of subjects.

Calcium supplements and bone mineral density (BMD)

The importance of the calcium intake during adolescence has been evidenced by a recent double-blind randomized controlled trial on 220 Chinese teens showing that, after two years of low, medium or high calcium intake levels, the BMD increases in female adolescents who ingested more calcium (28, 29). In keeping, some data suggest that BMD is reduced and the fracture is increased in adult women who drunk less milk during childhood and adolescence (30).

Even in adults, BMD has been suggested to be possibly influenced by calcium intake. Indeed, in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study on more than 36 000 postmenopausal women BMD at hip was slightly higher in the calcium plus vitamin D group than in the placebo group (31).

In a more recent study on about 7000 subjects older than 50 years of age, a calcium intake below 400 mg/day was associated with lower BMD and femoral cortical thickness, while a calcium intake above 1200 mg/day was positively correlated with BMD (32). In keeping, the meta-analysis from Shea and coauthors found that calcium was more effective than placebo in reducing the rates of bone loss after at least two years of treatment, with a difference in percentage change from baseline of 1.7% and 1.6% for spinal and hip BMD, respectively (33).

Another five-year randomized controlled trial on about 1450 elderly women reported an improvement in ultrasonographic parameters related to bone density in women with an adequate (>80%) compliance to the supplements, suggesting that adherence to treatment is crucial for the therapy to be effective (34). Similarly, a recent meta-analysis of nine studies showed that supplementation with calcium plus vitamin D, has a small-to-moderate effect on spinal and femoral BMD in healthy males (35).

Partially in discordance, in the meta-analysis of Tai and coauthors (including 59 studies) increasing calcium intake from dietary sources increased femoral BMD by 0.6–1.0 and femoral and spinal BMD by 0.7–1.8% at two years, but the increase in BMD at later time points was similar to the increase at one year (36).

Overall, these data suggest that calcium supplement have positive effects on BMD, which is probably more important in subjects with adequate compliance to the supplements and with baseline lower dietary calcium intake (8).