Tara Haelle

Aug 19, 2016,

A vitamin supplement typically conjures up an image of pills you swallow or perhaps a chewable multivitamin, but that’s not the case for vitamin K administered to newborns. It does come in oral form, but it’s the vitamin K shot that’s most common and most effective—and most recently in the news.

Many people don’t even realize that newborns receive a vitamin K shot at birth even though it’s been recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics since 1961. And for most of the time since then, no one really questioned the potentially life-saving intervention. But a small yet concerning uptick in parents refusing the shot has occurred in recent years, as I’ve written before in 2013 and in 2014.

Now a new study in the Journal of Medical Ethics explores the reasons that somewhere between 0.5% and 3% of parents decline the shot. The reasons range from faith-based ones to beliefs that it’s “unnatural” to anxiety about pain and possible side effects. The best antidote to fear, misinformation or a general lack of information is knowledge, so let’s review the basics of what vitamin K is, why it’s needed and what it does—and doesn’t—do. Much of this information is available is also covered in the book Emily Willingham and I wrote, The Informed Parent: An Evidence-Based Resource for Your Child’s First Four Years, and the study references are available here.

What is vitamin K?

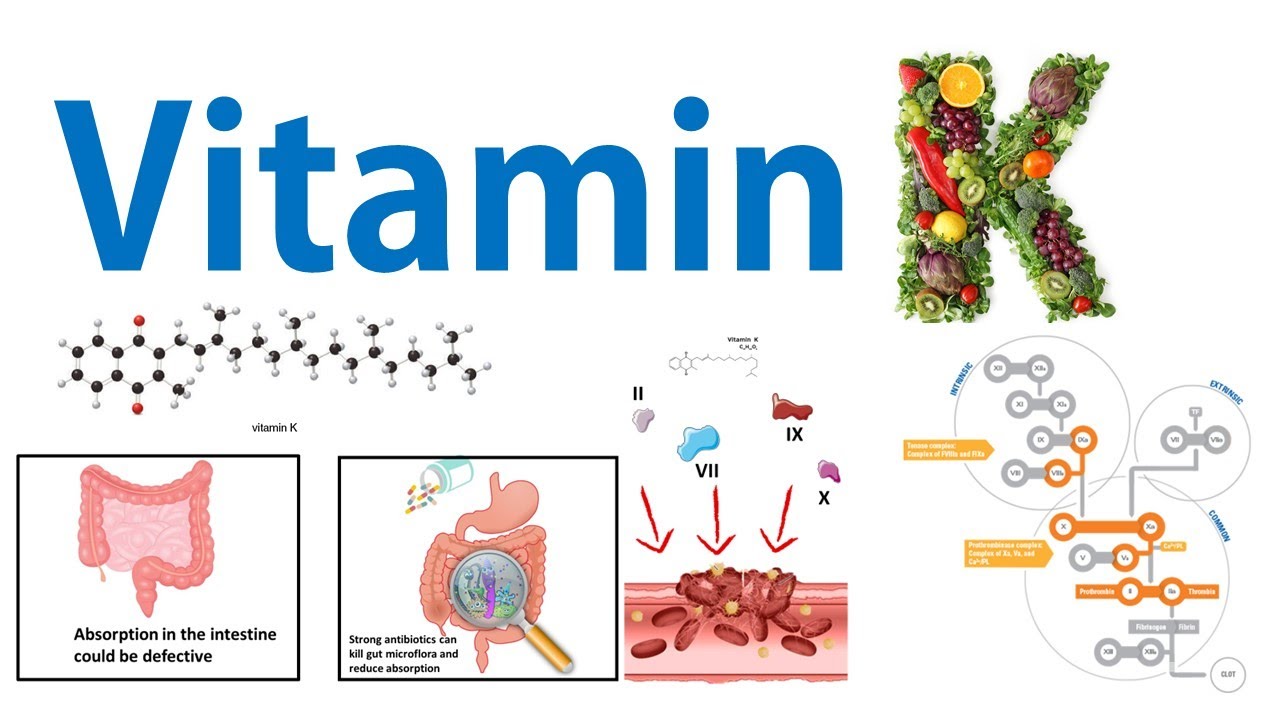

Vitamin K is a fat-soluble vitamin that’s actually named after what it does: Koagulation, the German word for coagulation. It activates the molecules (clotting factors) that allow our blood to clot. If our vitamin K levels drop too low, though the threshold varies from person to person, we can spontaneously bleed internally. We get about 90% of our vitamin K from diet (mostly leafy green vegetables) and about 10% from bacteria in our intestines.

Why would babies need vitamin K right after birth?

The vitamin is metabolized and stored in the liver—not free-floating throughout the body—so almost none of a pregnant woman’s vitamin K crosses the placenta. All babies are therefore born vitamin K-deficient, putting them at risk for uncontrolled bleeding, called vitamin K deficiency bleeding, if their vitamin K levels drop too low and they have not received a dose to hold them over until they’re eating solid foods (and their livers have developed sufficiently to extract and use the vitamin K in food). Though uncommon, vitamin K deficiency bleeding can have catastrophic consequences, potentially resulting in gross motor skill deficits; long-term neurological, cognitive or developmental problems; organ failure; or death.

How common is vitamin K deficiency bleeding?

The three types of vitamin K deficiency bleeding—early, classic and late—can occur in the brain or in the gut. Approximately 0.25% to 1.7% of newborns who don’t receive vitamin K at birth will experience classic or early vitamin K deficiency bleeding. Classic is within the first week after birth; early is in the first 24 hours. However, nearly all early vitamin K deficiency bleeding is secondary, which means the newborn has an underlying disorder or was born to a mother who was taking medications that inhibit vitamin K, such as anti-epileptic drugs, some antibiotics, tuberculosis drugs such as isoniazid or blood thinners such as coumarin or warfarin.

Late vitamin K deficiency bleeding, occurring when a baby is between 2 and 24 weeks old, affects an estimated 4 to 10 of every 100,000 babies who don’t receive vitamin K at birth. About one in five babies who develop late vitamin K deficiency bleeding die, and two of every five who survive have long-term brain damage. Because it’s rare and internal, it’s always easy for the bleeding to go undiagnosed for too long, which probably contributes to the high mortality and long-term effects. The treatment for the bleeding is vitamin K.

What did babies do before we gave the shot?

They died or suffered the other serious long-term consequences mentioned above. Babies have always been born deficient, but again, it’s easily missed or misdiagnosed, so the condition flew under the radar for most of human history. When first discovered in 1894, vitamin K deficiency bleeding was called hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. Even then, infants suffered so many other complications and diseases before vaccines and other medical advances were widely available that such a rare condition didn’t garner much attention or resources. As neonatal care improved, it became an unacceptable risk, and we learned in 1944 how to prevent it.